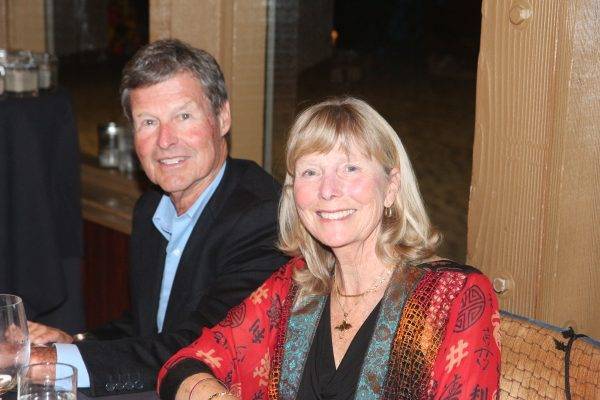

Richard Stephens made Cannery Row Studios a haven for local artists

Cannery Row Studios was located on the site of a former lumber mill, built in 1921 at Francisca and Catalina avenues in Redondo Beach, behind the AES Power Plant. The lumber mill became Weddle Woodcraft, which closed in the early 1970s. The south side of the property then became the Redondo Beach Technology Center. The mill’s two remaining warehouses, on the north side of the property, became the Cannery Row and 608 North art galleries.

Cannery Row was helmed by Richard Stephens for roughly 20 years. During that time, hundreds of local artists had their latest works exhibited. For “Cannery Row Revisited,” which opens Saturday at SoLA, Stephens has selected 25 of those artists for a look back at an important chapter in the history of art in the South Bay.

This was a sleepy part of town for many decades, but now the long vacant land behind the gallery warehouses is a shopping center with restaurants, shops and a car wash. Call it progress or not, but when old buildings change or disappear memories of what they once contained start to go with them.

“If we live long enough we see the beginning of things,” says former Cannery Row artist Patty Grau, “and the end of them, too. Dive bars, taco stands, beach cottages and Cannery Row Studios… The artists were happy. The parties were legendary and didn’t end when the police came and told us to close it down. We just closed the doors and went inside.”

“The exhibition,” she adds, “is meant to reflect on 20-plus years of a disparate aesthetic, a non-conventional tradition, and a historically relevant part of South Bay art culture.”

Writing in 2010, Renee Moilanen of the Daily Breeze called Cannery Row “a charming misfit,” and that, by being “part art gallery, part artist studio, part motorcycle repair shop, part storage shack and part school,” it defied categorization.

Earlier this year, Zask invited Stephens “to curate this show in order to recall the memories and the people who were involved from the beginning.”

Which is to say it evolved to reflect the personality and character of the man who kept it going through times tough and more tough.

Okay, the story of your life, let’s go!

“Well, it’s the story of Cannery Row,” says Richard Stephens, with a laugh; “it’s not the story of my life.”

We pause while a nearby motorcycle drives off. A fitting prelude.

“Back in the late 1980s, my friend Paul said, Go down to Francisca and give this guy $500 and you’ll get a space in this warehouse. I was in Westchester, just hating where I lived. I said, Okay, and I went down there.”

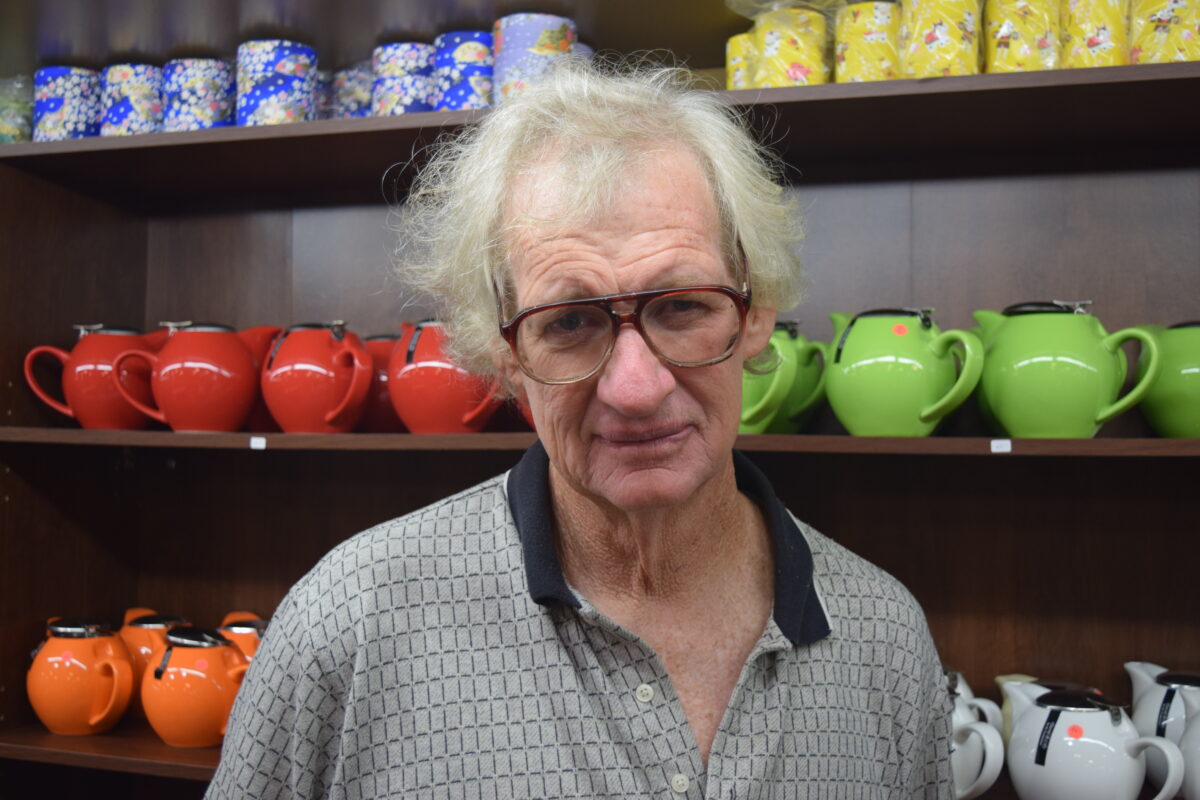

He forked over the dough and moved in. Pete Chambers had rented a section of the warehouse a couple of years earlier, in 1988. “Pete’s friends were Wilfred (Sarr) and Robi (Hutas) and Frank Minuto and a whole bunch of other artists,” including Paul Orvalla, all of whom were a generation older.

As for the name of the gallery, Cannery Row Studios, that was Orvalla’s idea, Stephens says. “The movie (based on the Steinbeck novel) had just come out, and we were like all the bums in the movie.” But what the name really came to reflect was a fast-vanishing bohemian lifestyle which was, in fact, fairly prominent in Hermosa and Redondo during the 1960s and 1970s (and earlier, actually). So when people in the 2000s say “keep Hermosa, Hermosa,” that train left the station a long time ago.

Once he’d settled into his new digs, Stephens said to himself, “I’ll put up with anything to be here; and I had to put up with a lot. Slowly we gained control over the whole front of the building and that became the gallery and the studios. I just kept on remodeling the place and making it better.”

Keeping the nearly century old building from falling down required plenty of work, much of which Stephens did himself. When he needed an electrician he enlisted John Teague, a local artist and surfer. Stevens offered him a show in exchange for his services. “It was kind of a barter system that ended up building that shop.”

“I had about a six- or seven-year run of really good shows,” Stephens says. Robi Hutas and Wilfred Sarr were among the artists whose work was often shown, but as Bob Mackie says, “The shows were eclectic,” and as Ben Zask notes about the gallery, “It was diverse and people from all walks of life were there: old, young; conservative, radical; poor, rich; educated, dropouts. All shared the same space.”

One month it could have been an exhibition devoted to the Twigs art group, comprised of several notable, older artists, and the next month work from the local high school art departments.

“I was an independent studio and gallery owner,” Stephens says. “If I liked the concept I’d try it out.”

“Richard was very accommodating to the artists’ preferences in hanging and helping them get the exhibitions up and ready for the opening,” says Bob Witte, who frequently shows with the Twigs. At greater length, as Witte recalls, “How did it come about that Allen Bollinger, Aldo Favilli, Winston Marshall, Frank Matranga, Michael Rich, Mariann Scolinos and I had an exhibit at Cannery Row? As we remember it, Richard Stephens called and asked if we wanted to put on an exhibit. Of course the answer was ‘you betcha.’ Cannery Row wanted to include us to help round out it’s eclectic selection of artists who show in the South Bay.

“The gallery had the spaces that we needed to be able to show off the large paintings, medium size ceramics, digital art, wall sculptures and the smaller photographic works,” Witte continues. “The space worked great for the large paintings and wall sculptures that were bathed in the natural light of summer with the big garage door open. The small backroom found spaces for the digital and photographic works where, the somewhat uneven track lights could illuminate each piece.”

Another person who would play a key role in Stephens’ Cannery Row years was Jon LaMar. “I met him at Java Man (in Hermosa Beach). He had a show there and I saw his work, and I said, Come to my studio, you can have the whole front yard; just do what you want.”

LaMar did precisely that, adding some character to the front yard with his sculptural pieces. But he did more than that, too. “He loved our art,” Stephens says, “and he started buying everybody’s art.”

Meanwhile, the responsibilities of running a gallery by himself began to take its toll. “I was doing everything, because it was easier [that way],” Stephens says, although this also increased the strain. “I broke a foot… fell off a few ladders.”

“That’s the basic reason why I left. I knew that I needed to get out of the place, but I didn’t know how. I couldn’t just leave it. I wanted to leave it to somebody who would maintain it, because I got it to a certain level.”

(Luckily he did find someone to whom he could pass the torch. As Peggy Zask notes, “Even after John Cantu took over the space for Ego Gallery, for a few years it maintained that non-conformist free spirit.”)

However, it was LaMar who provided Stephens with a way out. One day he took Stephens aside and, as the latter recalls, “He said, You’re not looking so good, Richard; why don’t you come and sleep at my house for a while? So I came to the house in North Redondo.”

Not long after, LaMar moved into his aging mother’s home in Long Beach to look after her, and Stephens then rented the house. “I brought Robi (Hutas) along because Robi had lost his place in Hermosa when his landlord died.”

Running a gallery in an old warehouse is one thing, but living in a cold, dirty, nearly-century-old warehouse is another, and Stephens, who hadn’t lived in a real house for 20 years, jumped at the chance to move.

Around this time the vacant land behind Cannery row was about to be developed, which implied an onslaught of construction noise.

“When that got approved, I went, That’s it for me, I’m out of here,” Stephens says. “‘Cause I was trying to do both; I was trying to stay at the shop but also be at the house.”

He then said to John Cantu, “Here, it’s yours, here are the keys, you have a complete gallery.” Beginning in 2013, with the help of Emiko Wake, who brought in many Japanese artists, Cantu filled the gallery with show after show, highlighting his own work as well as artists such as Michael Chomick and Scott Trimble. The opening receptions were boisterous and impassioned, a last hurrah for the bohemian joie de vivre in Redondo Beach.

“He lasted two years and he has a gallery in Tokyo now,” Stephens says of Cantu. “I was the best thing that ever happened to him, but he doesn’t see it that way. Such is life.”

Perhaps mentally and spiritually he did make the move, but physically he stayed put.

“Right,” he says. “I just didn’t want everybody to know that I might die. But I didn’t, so now I’m reasserting myself back into the business.”

“I went to have my first heart surgery after that,” Stephens says. “Then I had a second one. And now I feel pretty good.

“So that’s an abridged story of mine… how things went with Cannery Row.”

LaMar never came back from Long Beach. He took his own life. Stephens is still at the house in North Redondo. For the past three years or so he’s been working out of the studios at Destination: Art in Old Torrance.

“Cannery Row Revisited” will offer an opportunity revisit the art and the stories behind.

Photographer Don Adkins was in two shows at Cannery Row, one of them a two-person show with Frank Minuto, the second a solo show with 70 images spotlighting live performances by rock ‘n’ roll musicians.

“Richard was so helpful in working with us to hang a very cohesive and exciting exhibition,” Adkins says. “This first-ever experiment worked as opening night was packed with over 200 attendees… Both shows highlighted what Richard Stephens brings to the table, a vision and the ability to take chances for the betterment of arts in the South Bay, support to artists and to those who love the art experience here where we live.”

Lastly, as Peggy Zask aptly phrases it, “Cannery Row Studios was truly a South Bay rarity. We are happy to host this show to give tribute to something culturally low-key, but powerful.”