The art of invention, the invention of an art

Photographer Hippolyte Bayard at the Getty

by Bondo Wyszpolski

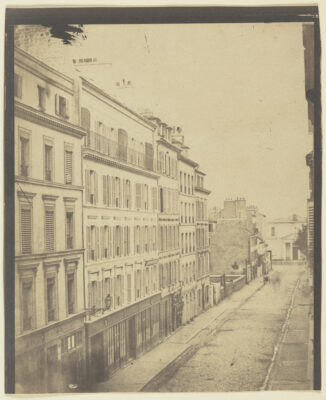

It’s a different kind of “Wow!” when you see the work of an early photographer whose every image was still an experiment with chemicals and equipment. The birth of photography — the Big Bang of a new artistic medium — isn’t easy to imagine today when cameras are ubiquitous and the world is bombarded with images. But once upon a time…

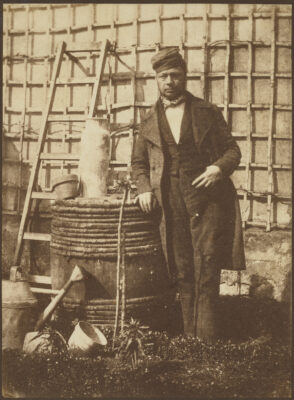

“Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer” is on view at the Getty Center through July 7. Bayard (1801-1887) was among the early birds of photographic innovation, but by and large he’s been running in the shadows of William Henry Fox Talbot and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, among others.

In the catalog that accompanies the Getty exhibition, Éléonore Challine notes that Bayard, if we exclude writeups in newspapers and journals, was “the first nineteenth-century French photographer to be the subject of a monograph.” With Bayard, she says, it’s an “eternal rediscovery.”

No one’s out to elevate him to the head of the pack, but his contributions to the medium are outstanding. As Karen Hellman notes, “Bayard’s direct positive process on paper is the method most unique to Bayard and the one with which he is frequently credited in histories of photography… He employed silver chloride to blacken the paper in the sun and then dipped the sheet in potassium iodide before exposing it in the camera obscura.” I’ve slipped in this last tidbit because there was an involved process — hoops and ladders, if you will — to coax an image to fruition. For the eager among us, there’s a lot of science in the show and in the book.

And speaking of the book, this catalog is the first book about Bayard to appear in English.

Anyway, everything got cooking in 1839, despite primitive stabs at the photographic process before then. In August of that year an art show took place in Paris to benefit the victims of an earthquake that struck the island of Martinique. Bayard displayed 30 examples of his direct positives, and whatever fanfare about it there was at the time I don’t know, but this was the very first exhibition to showcase photographic work.

This is not to take anything away from Talbot and Daguerre, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson and their confrères, but most of them have been basking in the limelight for years.

The 1840s saw quite an advancement in camera technology, and there was certainly some rivalry, aired in public or behind the scenes. Bayard was accused of not having a scientific background (a roundabout way of calling him an amateur), and this happened because he didn’t readily reveal or publish his methods and process. But are inventors supposed to be team players?

I don’t think that Bayard was out for fame and fortune, but he did seek recognition for his discoveries. As noted by curators Hellman and Carolyn Peter, “Between 1839 and 1851 Hippolyte Bayard sent a series of letters to the Académie des sciences outlining his recipes for photographs on paper,” and several of these are reproduced in full (translated) at the end of the catalog.

In October, 1840, Bayard created what many consider his most famous image. “Le Noyé” (or “The Drowned Man”) is a kind of fake-news selfie in which Bayard has depicted himself as a suicide victim ostensibly dredged from the Seine and propped up, half-naked, on a chair in the morgue. Based on what is inscribed on the reverse of the photo, the image is cleverly satirical because it shows the artist as neglected, discarded, and waiting to be identified. As a staged work, with universal associations for most of us working in the arts and going unnoticed, it’s a little gem.

Okay, here’s something important I should have mentioned earlier. It was only in 1984, under Weston Naef, that the museum’s photography department got rolling, and one of the first acquisitions was the album “Dessins photographiques sur Papier: Recueil No. 2,” which contained 145 photographs attributed to Bayard — and these comprise the bulk of the current show. Altogether, the Getty possesses 190 images taken by Bayard, and it’s the second-largest collection of his work, with the biggest one being held by the Société française de photographie. A digital facsimile of the Getty album can be accessed online.

It need hardly be said, but most of those images are monochromatic and hazy, and some have faded faster than an old pair of jeans. Studies were undertaken to determine which pictures could be safely displayed and which were too light-sensitive for public viewing.

The art and science behind photography developed rapidly, and Bayard’s “Self-Portrait with the Legion of Honor” (c.1863-69) has sharp detail and good contrast: a huge jump from humble beginnings.

The catalog for the show, “Hippolyte Bayard and the Invention of Photography,” should appeal to a wide audience. It has an informative, well-illustrated chronology to put matters in perspective, contains a dozen short essays, and in some ways it complements the Camille Claudel sculpture exhibition that’s currently on view. The only misstep is the inclusion of a conversation with L.A.-based Paul Mpagi Sepuya (b.1982), an African-American photographer whose points of reference don’t align with Bayard’s work or mindset 180 years ago. Caroline Peter remarks that “When you start putting together the dates and thinking about what was happening in the United States, Africa, Central and South America, what was happening in the ocean, the slave trade, revolutions, and moving ahead into the Civil War, it is important not to isolate all those different things happening at the same time.”

Sorry, no, and bringing up George Floyd and COVID doesn’t add to our understanding and appreciation of a seminal, still little-known midwife (one of several) to the birth and development of photography.

Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer is on view through July 7 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Humans get in for free; your horse pays to use the stable. (310) 440-7300 or visit getty.edu. PEN