Tough love and good groundstrokes

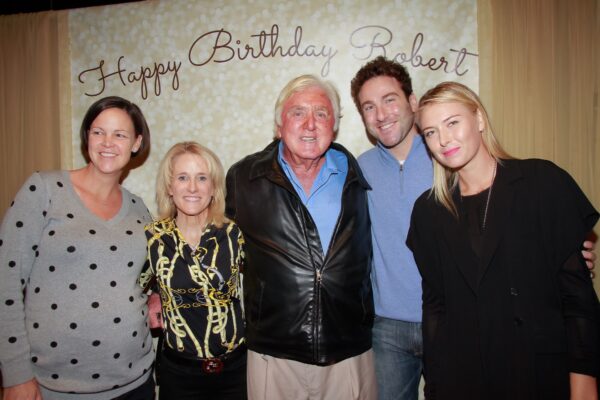

Pictured from left are tennis greats Lindsey Davenport, Tracy Austin, their former coach and honoree Robert Landsdorp, Justin Gimelstob and Maria Sherapova.

When Robert Lansdorp’s daughter Stephanie threw a surprise 75 th birthday party for her dad at the West End Racquet & Health Club last November 15, it quickly morphed into something much more than just a party.

“It became a celebration of his life and the positive influence he’s had on so many people,” recalled Tracy Austin, one of four junior players Lansdorp put on the path to number one in the world – the only tennis coach ever to accomplish that feat. “I really think at that party everything in his life came full circle for him. I even saw a few tears come out of his eyes.”

Former student Jeff Tarango had a similar impression.

“Seeing all those players he had developed together in one room served as justification for all those years he acted so crusty and crabby,” Tarango said. “I never took it seriously when he would yell and scream. I used to laugh because it was an act designed to make us better players. And then he would yell at me for laughing at him when he tried to act tough.”

Lansdorp said he learned something that night that he never fully understood until his former students made it clear to him. Known as the guru of groundstrokes, a coach who built his lessons around developing muscle memory through endless repetition and painstaking attention to detail, Lansdorp said not one of his former students at the party thanked him for teaching them the mechanics of a world-class forehand, backhand or serve.

“All of them thanked me for making them tough, for giving them confidence, for being able to survive in this world,” Landsdorp recalled. “I guess that’s what I’m really about — but not purposely, it just comes with the teaching and the coaching. Everything else is just strokes, strokes, strokes.”

Lansdorp, who proudly cultivated his reputation as a fearsome, fire-breathing tyrant who drove his students unmercifully, said there was no debate about the mentally toughest kid he ever coached.

“Tracy was the toughest ever. She was unbelievable, so much tougher than anyone else it was a joke,” he said in his uniquely accented Dutch-immigrant-meets-American-hipster voice. “I was always tougher with the really talented ones, and I was toughest of all with Tracy – because she could take it.”

Austin, whose decade with Lansdorp started at the Jack Kramer Club in Rolling Hills Estates in 1970 when she was seven years old, recalled that her most challenging moment came early on when she started hyperventilating and Lansdorp insisted on continuing the lesson.

“I couldn’t breathe, but he just said to get back out there,” Austin said. “I started thinking this is a bit too much.”

Lansdorp broke the tension by joking that next time it happened he would put a paper bag over her head, and soon they were back to building the two-handed backhand and refuse-to-lose game that enabled Austin to shock the sporting world by winning the 1979 U.S. Open at age 16, making her the youngest U.S. champion ever – a record that stands today.

Austin, who still lives on the Peninsula, said Lansdorp was in the stands in New York when she won that first U.S. Open. “He was very nervous before I won,” she said. “As a coach, that was such a special moment to share with a pupil. For the first time I think he really felt that he had achieved something in this game.”

Teaching grit

Three of his big four prize pupils – Austin, Lindsay Davenport and Maria Sharapova – attended the birthday party, with only Pete Sampras missing. But among the crowd of more than 150 friends and family it was a couple of lesser lights, Tarango and Kimberly Po – kids who went on to good but not great careers – whose presence made Lansdorp feel especially proud.

“Kimberly Po is an even more inspiring success story than someone like Pete or Tracy,” Lansdorp declared last week during a long interview at his Redondo Beach home. “Kim was a good junior player, but nothing really great. I kept her on because she was so smart and tried so hard.”

After attending UCLA for one year, Po informed Lansdorp she was turning pro.

“I said that’s great, that’s fantastic, but I really didn’t think she’d do much on the tour,” he said.

Amazingly, within a few years Po had reached a career high ranking of 14 th in the world in singles and sixth in doubles. She was even seeded at the U.S. Open.

“I use that example for these kids I work with now,” he said. “That’s why I don’t give up on kids easily. I keep plugging away, because sometimes something totally unexpected like Kimberly Po happens. She decided she wanted to be on the pro tour, and when they decide that they want to do it, rather than their parents wanting it, all of a sudden it’s their show and things can completely change.”

Po remembered that she wanted to quit her lessons with Lansdorp after just one day.

“He was cursing a lot. He wouldn’t allow water breaks and he never said ‘good shot,’ just grunted when I hit a ball well,” she said. “I was really intimidated.”

The 11–year-old Po begged her parents not to drive her to lessons the next day.

“But my dad said he could already see how much better my strokes had gotten in one day, so I finally went back and stayed with him.”

Wimp vs. hunk

Tarango, who Lansdorp nicknamed “stone hands” because he had trouble learning to volley, still lives in Manhattan Beach and has carved out his own successful career as a tennis teacher. He recalled an incident that he said summed up Lansdorp’s grit-and-grind philosophy.

“There was one day he came to the courts and most of the girls were all gaga over Brian McPeak, this tall studly dude,” Tarango said. “Suddenly Robert turned to the group and said you need to learn the story of the hunk versus the wimp.”

Declaring that Tarango would play McPeak one set and the loser would have to jump into the pool in full tennis gear, Lansdorp made every girl there vote on who they thought would win. All except one voted for McPeak.

With all the kids watching, the two boys played a tense, hard-fought set that Tarango eventually won 6-3, setting up Lansdorp to deliver the lesson of the day.

“He said the wimp always tries harder, isn’t afraid of losing to the hunk, and doesn’t get nervous playing the hunk – he just wants to beat the hunk.”

Undaunted

Five days a week Lansdorp drives up to a private court in Palos Verdes and gives lessons for up to eight hours a day. So why does he still stand under the hot sun that already gave him skin cancer on his lip, leg and shoulder and hit balls and yell instructions at kids who have a better chance at winning the lottery than ascending to the tennis heights?

“Sometimes I do ask myself what the hell I’m still doing out here,” he admitted. “But I don’t think I can ever retire because I still enjoy improving kids, still love that feeling of helping make somebody better. Maybe it’s because I’m getting so freaking old, but I’m still looking to develop somebody who could give me five number ones.”

He started laughing when asked if he has any potential number ones in his current crop.

“There is one little girl from Canada, 10 years old, very, very tough — almost too tough,” he said. “She wasn’t allowed to play for three weeks after she told an umpire to get off the court because he overruled her about six times on line calls and she didn’t like it.”

He shook his silver-maned head in amazement and bad-boy approval.

“She asked him why don’t you just get off the court?” he said. “Unbelievable.”