Getty Museum’s “Gardens of the Renaissance” a pleasant excursion

“Insect, Tulip, Caterpillar, Spider, and Pear” (1561; illumination added 1591-96)), by Joris Hoefnagel and Georg Bocskay. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

This is a quiet little show, partnered with a slender book of the same name that invites us to linger among its pages as we would in an actual garden. As Getty director Timothy Potts notes in his foreword to our visually aromatic tour, “The volume gathers a wide range of objects from the Getty’s permanent collection made between 1400 and 1600, with a focus primarily on the art of Renaissance book illumination.”

There are 64 color reproductions in Bryan C. Keene’s Gardens of the Renaissance, a most ephemeral subject, and those gardens depicted – if indeed they truly existed as such – are long gone. They are, however, preserved artistically, pressed between the pages of prayer books that have retained their often vibrant hues simply because they are closed when not in use as opposed to being left open by the window on a bright day in July.

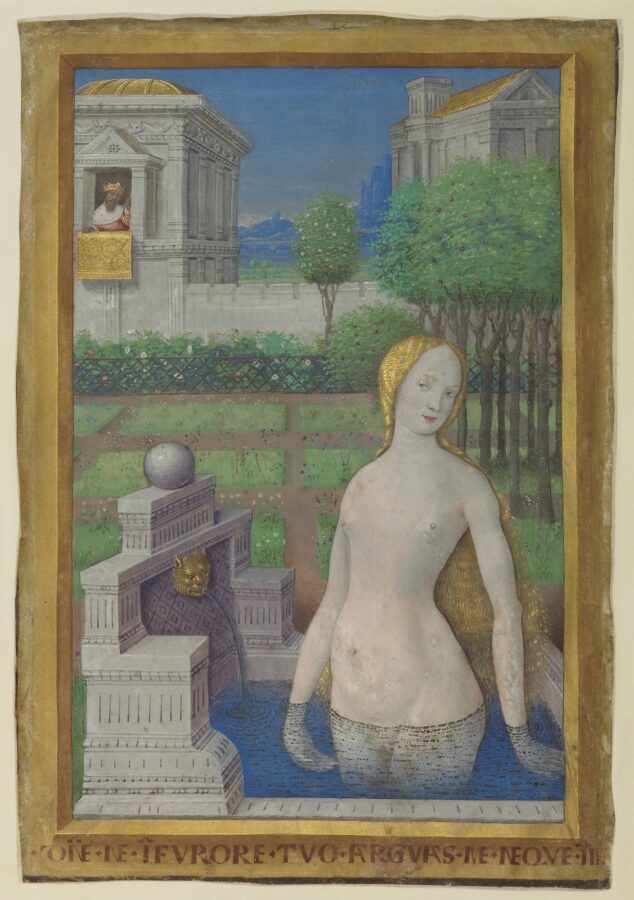

“Bathsheba Bathing” (1498-99), by Jean Bourdichon. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Needless to say, religious imagery prevailed. Floral abundance seems rooted in the pristine Garden of Eden, and not surprisingly the book and the exhibition are primers in religious symbolism. For example, as Keene writes, “In Annunciation scenes, Mary is often seen near an enclosed garden because Christian tradition associates the private green space with purity, prayer, and paradise, the latter of which awaits Christians in Heaven.”

Medieval cloister gardens, therefore, “were referred to as paradise on earth, walled spaces where monks could meditate and pray,” which for me brings to mind that exquisite, open-aired enclosure atop Mont St. Michel in Normandy. Either way, these are little ports of refuge where we can tether our storm-tossed ships of self.

“Noli me tangere” (1469), by Lieven van Lathem. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

While poor folks, then as now, assiduously hoed their patch of ground and harvested a few tomatoes, “Gardens at Renaissance courts,” says Keene, “were planted as signs of magnificence, as displays of power and control over the natural world, and thus are demonstrations of order.” Telling, also, are the images herein of courtly spaces, villas, and châteaux: “The combination of sculptures, fountains, and topiaries in gardens not only communicated the patron’s control over nature but also expressed the Renaissance ideal that art and nature are in a constant back-and-forth duel of imitating each other.”

As far as what grew, both in the wild and under Mankind’s green thumb, this was determined largely by geography, by terrain and temperature. Of course Mother Nature always had the last word and could at any moment intervene – with biblical droughts or flooding – and wipe everything out.

Jesus Christ has at times been depicted as a gardener (an illustration on view shows him with a shovel), just as on other occasions he has been portrayed as a shepherd, a carpenter, and a bus driver. However, one thing that neither Jesus nor other gardeners of yore possessed in their arsenal of gardening tools was a leaf-blower. Whatever happened to the rake, my dear friends? And when my neighbor is in his backyard I’m never sure if he is mowing his lawn or testing out an airplane engine.

“The Adoration of the Magi” (c.1480-85), by Jean Bourdichon. Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The scope of this well-manicured presentation falls shy a century or so before the European fashion for garden follies, those artificial ruins and impossible garden furniture that I like to refer to as outdoor theater. Meanwhile, many of us suffer quietly in this concrete jungle where true greenery huddles in secrecy or cringes in fear.

Gardens of the Renaissance is a pleasant excursion, the exhibition being on view through August 11 in the J. Paul Getty Museum in the Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles. Bryan C. Keene’s slim hardcover book clocks in at just 78 pages and sells for $19.95. In conjunction with the show, the Getty Center’s central garden has incorporated new plantings of Renaissance-era herbs and flowers. Now, if only the book included a couple of scratch-and-sniff pages we’d be all set. Since it doesn’t, an outing to the garden itself is all but mandatory.

(310) 440-7300 or go to getty.edu.